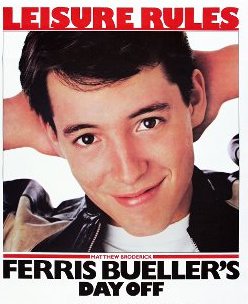

The Ferris Bueller Guide to Smarter Storytelling

By Rob Biesenbach

October 2023

There’s a wonderful scene in the classic American ‘80s film “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.” If you haven’t seen it, then drop what you’re doing right now and stream it!

As part of their awesome day off in Chicago, Ferris and his friends visit the Art Institute, where Cameron becomes immersed in the impressionist masterpiece “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” by Georges Seurat.

Painted in the pointillist style, the canvas appears up close to be nothing more than random colored dots — which, according to writer/director John Hughes, symbolizes Cameron’s despair over the perceived meaningless of his existence.

Only from a distance do we see that the dots come together to form the idyllic waterfront scene we’ve come to love.

This illuminates a common communication problem: Too often, we’re focused on the dots (the small details, the data, the facts) when instead we need to step back and offer the big picture (the context, the meaning, the story).

What’s the larger issue we’re trying to communicate, the problem we’re hoping to solve, the issue we’re seeking to address? In other words, it’s critical to lead with the “why,” not the “what.”

Sort through the 5 Ws.

We’re all familiar with the classic “5 Ws” (and sometimes “H”) of journalism: Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?

Which is most important? It all depends. Let’s look at how a basic local news story about a car accident is covered:

- If it just happened, then a breaking TV news bulletin would lead with the “what” and “where”: “Traffic is stopped north of exit 17 due to a multi-vehicle accident.”

- If one of the drivers was a public figure, then they might lead with the “who”: “The mayor was involved in a multi-vehicle accident this morning.”

- Later on, they might get to the “why”: “Icing on expressway overpasses was to blame for a multi-vehicle accident early this morning.”

But a presentation is not a news story. Think of it instead as an op-ed: You’re looking to persuade, to bring them around to your point of view. So always lead with the “why.”

Which brings us to the benefit of narrative.

Use a simple narrative framework.

The heart of every great story is conflict, and we are hard-wired to respond to that conflict. Right/wrong, good/bad, this/that, then/now and, of course, the mother of them all: problem/solution.

So before getting down into the weeds (or the dots), start with the power of narrative to paint the big picture and capture people’s interest:

- This/that: “In the past, we’ve opted for a careful, incremental approach. But we’ve determined that our biggest risk right now is not taking a risk. We recommend an aggressive strategy.”

- Them/us: “Most accounting firms bill by the hour, which we’ve found increases the cost to the client and hinders communication. We’re different. We charge a flat fee so there are no surprises. Here’s how it works.”

- Problem/solution: “Our declining number of young members threatens the association’s future. To win them back, we need to shake up our offerings. Here are our recommendations.”

Once you’ve established the context, then you can get into all the other details.

Also, note the order in these examples: problem, then solution. We often jump straight to the solution, recommendation or benefit. But you can’t get buy-in for a solution if the audience doesn’t recognize the problem.

Add stories.

Beyond the overarching narrative, you will also need specific stories to bring your point to life. That could mean:

- Pointing to a peer that went out of business by following the safer route

- Telling the story of a new client that was attracted to the firm because they were frustrated by the costs of working with their former accountants

- Profiling a typical Gen Zer and showing how the current member benefits aren’t responsive to their needs

And now, to quote a post-credits scene from Ferris Bueller (*spoiler alert*): “You’re still here? It’s over. Go home.” (And watch the movie!)